What secrets do the Taj Mahal’s locked rooms hold?

Shawdesh Desk:

Do the chambers of one of the world’s greatest monuments hold any secrets?

Judges belonging to a high court in India don’t think so. On Thursday, they dismissed a petition filed by a member of India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) demanding the opening of doors of more than 20 “permanently locked rooms” in the Taj Mahal to find out the “real history of the monument”.

More pointedly, Rajneesh Singh told the court he wanted to check out “claims by historians and worshippers” that the rooms housed a shrine to Shiva, the Hindu god.

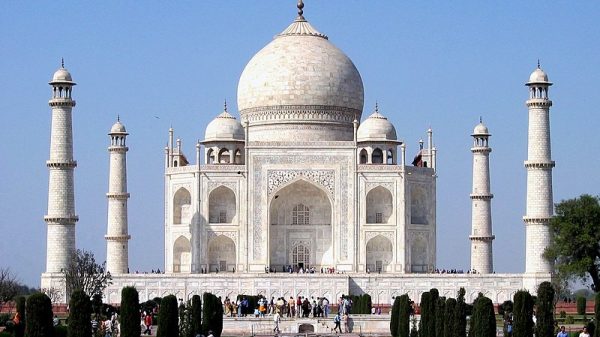

The Taj Mahal is a 17th Century riverfront mausoleum in Agra city which was built by Mughal emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his queen Mumtaz who died while giving birth to their 14th child. The stunning monument – built with brick, red sandstone and white marble and famed for its intricate lattice work – is one of India’s biggest tourist attractions.

But accepted history doesn’t impress Mr Singh. “We all should know what’s there behind these rooms,” he implored the court.

Many of the locked rooms that Mr Singh is alluding to are located in the underground chambers of the mausoleum. And going by the most authoritative accounts of the monument, nothing much is going on there.

Ebba Koch, a leading authority on Mughal architecture and author of a magisterial study of the Taj, visited and photographed the rooms and passages of the monument during her research.

These rooms were part of a tahkhana or an underground chamber for the hot summer months. A gallery in the monument’s riverfront terrace consists of a “series of rooms”. Ms Koch found 15 rooms arranged in a line along the riverfront and reached by a narrow corridor.

There were seven larger rooms extended by niches on each side, six squarish rooms and two octagonal rooms. The large rooms originally looked out onto the river through handsome arches. The rooms, she noticed, showed “traces of painted decoration under the white wash” – there were “netted patterns arranged between concentric circles of stars with a medallion in the centre”.

“It must have been a beautiful airy space, which served the emperor, his women and his entourage a cool place of recreation when visiting the tomb. It now has no natural light,” Ms Koch, who is a professor of Asian Art at the University of Vienna, noted.

Such underground galleries are familiar in Mughal architecture. In a Mughal fort in Pakistan’s Lahore city, there are a series of such vaulted rooms set into the waterfront.

Shah Jahan would often arrive at the Taj Mahal by boat on the Yamuna river, land on a wide flight of stairs or ghats as they are known in India, and enter the mausoleum. “I remember the beautifully painted corridor when I visited the place. I recall the corridor opening into a larger space. It was clearly the emperor’s passage,” says Amita Baig, an Indian conservator who visited the place some 20 years ago.

Growing up in Agra, Delhi-based historian Rana Safvi remembers that the underground rooms were open to visitors until a flood in 1978. “Water had entered the monument, some of the underground rooms were silted and there were some cracks. Authorities shut the rooms for the public after that. There’s nothing in them,” she says. The rooms are opened from time to time to carry out restoration work.

The Taj has its share of myths and legends.

They include Shah Jahan’s plans to build the “black Taj” opposite the present monument; and that Taj Mahal was built by a European architect. Some Western scholars have said it could not have been built for a woman given the inferior position of women in Muslim societies – this conveniently ignores other tombs for women in the Islamic world. At the monument, enthusiastic guides regale visitors with stories about how Shah Jahan killed the architect and workers after the building was completed.

In India, there have been persistent myths that the Taj was originally a Hindu temple, dedicated to Shiva. After Suraj Mal, a Hindu king, conquered Agra in 1761, a court priest is said to have suggested to convert the Taj into a temple. PN Oak, who founded an institute for rewriting Indian history in 1964, said in a book that the Taj Mahal was indeed a Shiva temple.

In 2017 Sangeet Som, a BJP leader, called Taj Mahal a “blot” on Indian culture as it had been “built by traitors”. This week, Diya Kumari, a BJP MP, said Shah Jahan had “grabbed land” owned by a Hindu royal family and built the monument.

These theories, says Ms Safvi, have regained fresh momentum among a section of the right-wing in the past decade or so. “A section of the right-wing is weaned on fake news, false history and a sense of Hindu loss and victimhood,” she says. Or as Ms Koch notes: “It seems that there is more fiction on the Taj than serious scholarly research.”

Leave a Reply